Shopify announced in March 2017 that it will be expanding its Ottawa headquarters by leasing new accommodations at 234 Laurier Avenue West which will increase its size by 325,000 square feet and about 3,000 employees beginning this year. This is fantastic news for Shopify, the Ottawa tech ecosystem, and the Greater Ottawa area in general.

Shopify is a tremendous Ottawa success story, and one that is transforming the city. Shopify began in 2004, went public in 2015 and has a market cap of CAN$ 12.8 billion (as of 05 June 2017). Shopify is rocking the Ottawa office leasing market in a variety of ways, one of which is its emergence as a dominant occupant of the central business district office space market.

Shopify describes itself as:

Shopify is the leading cloud-based, multi-channel commerce platform designed for small and medium-sized businesses. Merchants can use the software to design, set up, and manage their stores across multiple sales channels, including web, mobile, social media, marketplaces and physical retail locations. The platform also provides merchants with a powerful back-office and a single view of their business. The Shopify platform was engineered for reliability and scale, making enterprise-level technology available to businesses of all sizes. Shopify currently powers hundreds of thousands of businesses in approximately 175 countries and is trusted by brands such as Tesla, Nestle, GE, Red Bull, Kylie Cosmetics, and many more.

Now that Shopify has established itself as a large company with significant local buzz, we thought looking back on how they got here might reveal some quirks in the Ottawa office market. How did Shopify get noticed? When did that happen? How did that translate into interest from the office leasing market here?

Shopify: visibility as a tech firm raising capital

One way to track emerging firms is to follow their fund-raising activities, as raising money usually means expansion, and that means more employees, which means their existing accommodations may not suffice.

The tech funding scene is the domain of Crunchbase. It identifies the following rounds of funding for Shopify. We have supplemented this chart with the information from the initial public offering and the recent sale of treasury shares.

While the firm began in 2004 it did not secure Series A funding until late 2010. The dramatic round of funding is December 2013, by that stage Shopify was well covered by the local and national press as a potential unicorn, that is a private firm with a valuation of $1 billion pre-IPO. Based on the funding secured, Shopify became visible likely sometime in 2012.

Shopify: visibility as a tenant

Another way to track emerging firms is to follow which firms occupy what space in certain buildings, and as they expand they eventually become large enough to attract attention from the office leasing brokerage community. We believe that the transition into being a firm that attracts that interest depends both on the size of the firm, and where it is housed as it expands.

Shopify started as five people in 2004. Their first location was walk up 2nd floor office space above a coffee shop on Elgin Street. Their second location was walk up office space on Rideau Street. Their third location was the 2nd floor space in a two-storey building above a restaurant in the By Ward Market. Their fourth location was a “proper” office building in the By Ward Market, and it is only at this stage that the brokerage community started to notice them.

Around the time of their second location in the By Ward Market, Shopify had grown to 10,000 square feet and was occupying space in a building that the brokerage houses tracked. This move corresponds with the time of the Series A and Series B fund raises. The Series C fund raise saw the company expanding to 150 Elgin Street, a new Class A building in the Central Business District, while growth since the IPO and a market cap exceeding CAN$11 billion got them their next expansion to 234 Laurier Avenue West.

Visible versus invisible buildings

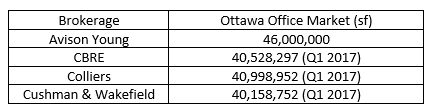

There seems to be no clear, common methodology for determining market inventory and vacancy rates

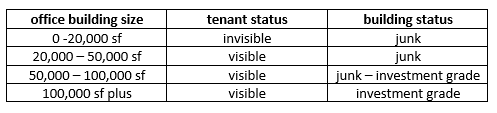

The commercial real estate brokerage community in Ottawa tracks most office buildings that are 20,000 square feet or larger. These buildings are included in the determination of vacancy statistics. They contact the owners for updates on availability, rental rates, operating costs and taxes, stacking plans, etc. usually once per quarter. It is easy to collect this information from the largest landlords with many buildings, while it is more arduous to maintain current information on buildings that are owned by entities which may only have a few buildings. These are the “visible” buildings.

The brokerage community arbitrarily decided that any building less than 20,000 square feet would not be included in their tracking. These smaller buildings are often mixed-use with retail on the ground floor with offices above, or they may be owner-occupied with some excess space available for lease. These buildings are effectively invisible to the brokerage competitive office market universe, as they are too small (adding little to available supply) and too difficult to track (too many smaller owners to track) quarterly.

The other invisible buildings are those that are deemed non-competitive, i.e. those buildings owned by the occupants or subject to such long-term leases that they do not compete for tenants looking for rental accommodations. These buildings can be large, like the Communications Security Establishment Canada headquarters at 900,000 square feet.

These last two categories comprise the “invisible” market.

The brokerage consensus view is that the competitive office market in Ottawa is 40.5 million square feet. This approach is excellent for office leasing personnel in determining where and when there is vacant space available to house tenants from mainstream owners. Its shortcoming is that it is not necessarily a good proxy for the universe of office building inventory in Greater Ottawa.

The dilemma then is attempting to sort out just how much invisible office space there is in addition to the visible competitive market. Altus deals with this in part by creating a G (government) class that is not in the competitive office market. As these are owned by the federal government and house lots of their employees, it does have an impact on the competitive market, similar to how a shadow anchor has impact on an adjacent mall.

We checked with Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC), which is the part of the provincial government that does property assessments to determine the tax base for municipal taxes. They track over 61 million square feet of office space in Ottawa. That means the invisible office market is about half the size of the competitive market here. Even netting out the federal government office building they own (17,400,000 sf), that still leaves about 3 million square feet of invisible office market inventory.

Visible versus invisible tenants

The world of tenant rep office leasing prospecting comes down to: find an office building; find the tenant directory; record the firms; get contact information; dial for dollars. The tenant rep coverage works in the visible market buildings as the firms they work for are good at collecting that information. Generally, the biggest tenants in town are in larger buildings, and if the smallest size office tenant that attracts consistent broker interest is 5,000 square feet +/-, you could assume that most of these firms are located in the buildings that are 20,000 square feet or more.

Maybe that assumption leads to coverage holes. Maybe there are many firms located in invisible buildings because those buildings cater better to smaller firms.

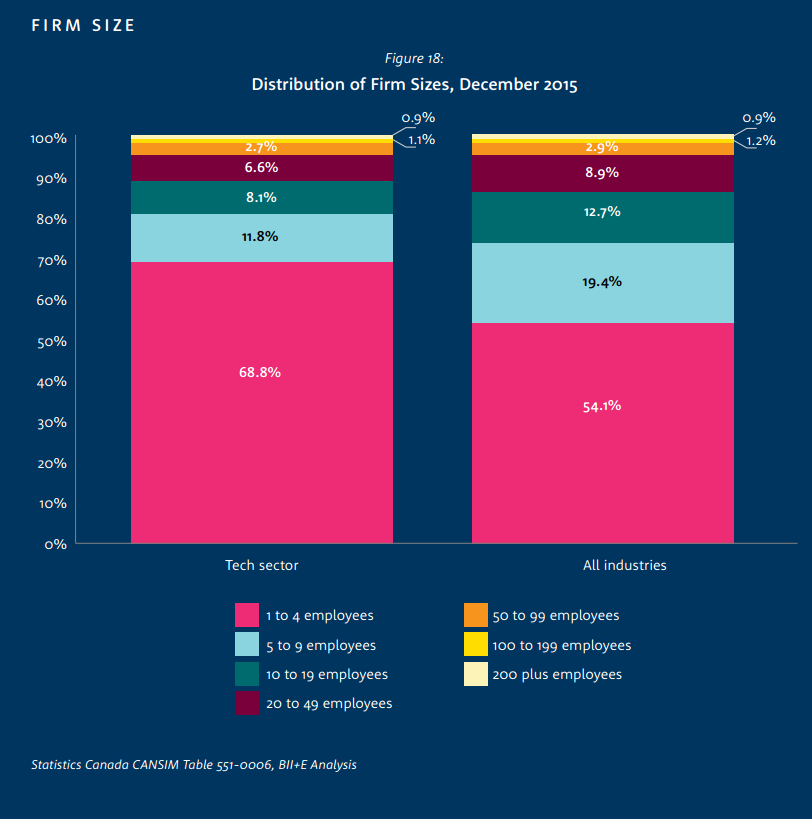

The following chart developed by the Government of Canada shows the distribution of firm sizes by employee counts. This means that between 85%-90% of the firms in Canada have less than 20 employees. If each company allocated office space at 200 square feet per employee, that means that about 90% of the firms in the country occupy less than 4,000 square feet.

This disconnect in the office leasing market means that most firms are not big enough to fit into the 20,000 square foot plus buildings that are tracked in the competitive marketplace. There are plenty of firms housed in the invisible office market, and possibly all those tech firms, like early-day Shopify, who do not yet have the scale to attract the interest of the brokerage community and the visible office leasing market.

There may be other Shopify’s starting to grow in places that are invisible to the office leasing brokerage community.

Borrowing Wall Street jargon: investment grade versus Junk

Seeing as tenant covenant strength – its ability to meet its financial obligations – is such a concern for building owners, maybe the approach by the bond rating agencies to creditworthiness should help sort out what terms or jargon would be best in this discussion.

Investment grade, bonds with relatively low risk of default, have a variety of credit quality ratings, with distinctions made between high quality (‘AAA’ – “AA’) and medium quality (‘A’ – ‘BBB’). Credit ratings below this level are low credit quality, and called non-investment grade, speculative grade, high-yield bonds, or junk bonds.

There is an equivalency in the commercial real estate world by which there are properties worthy of investment by institutions, hence being investment grade, and everything less than institutional investment grade, and for the purposes of this article, junk.

“Invisible” tenants in “Junk” buildings

Shopify began its life as an invisible tenant in a junk building. It took about 6 years to get to a stage where they were visible to the venture capital world. The funding rounds drove their growth to a stage that they occupied enough space in a visible junk building that they became visible to the office leasing brokerage community. Their IPO resulted in a transition to an investment-grade office tower.

Perhaps it is that ecosystem of invisible tenants in junk buildings that is a vital indicator for the strength of a local office leasing market, and is a market segment worthy of more research and tracking.

By the way, there is nothing inherently bad about being classified as “junk”. Most of the real estate world is classified that way.