Here in Ottawa the federal government dominates the office market. It employs roughly 140,000 people in a 700,000-person work force, its need for space is predominantly office, and in many ways drives innovation for the office market in terms of its standards for accommodations. Not surprisingly, private sector landlords pay close attention to federal government policies for the office space it occupies.

We review a recent policy change by the federal government in three stages:

- context for the policy;

- figuring out just how much private office space is affected; and,

- examining some of the nuances that have yet to be explored by this policy change.

CONTEXT

Each year, the Ottawa Real Estate Forum has a presentation made by Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), the department responsible for housing most employees of the federal government. This department was renamed after the last federal election, and was formerly known as Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC). The name change is still in the process of being completed, so the government may at times refer to PSPC or PWGSC.

Here in Ottawa, PSPC has “custody” of all the rental office space as well as a portfolio of owned office buildings. As the federal government has about 140,000 employees in Ottawa, this is a sizable requirement for office space and totals about 37 million square feet.

A complication for market analysts is that PSPC is not the only government department with “custody” for office space in Ottawa. There are crown corporations and some departments with custody for specific accommodations that form part of all the office space occupied here.

This quibble about “custody” is meaningful because it is always so difficult to sort through the impact of some policy decisions the government takes with regards to its office accommodations needs. The federal government is by far the largest occupier of leased office space here, and any change to the status quo is sometimes hard to appreciate, as well as its impact on any particular government department in any particular office building affecting any particular owner.

The broad sweep of what they intend to do is somewhat clear: what is difficult to discern is what happens in particular. The following attempts to provide context and perhaps even clarity for where the federal government is headed for office occupancy in Greater Ottawa.

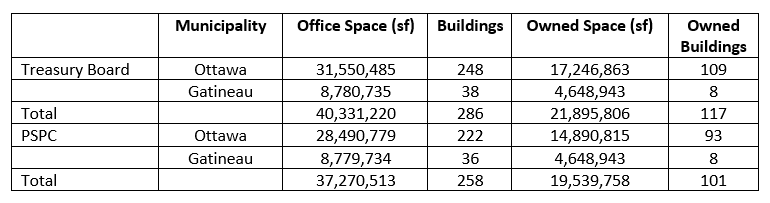

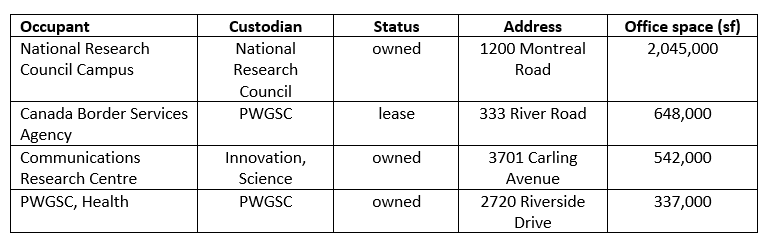

One of the slides form the PSPC presentation in October 2016 had the following information:

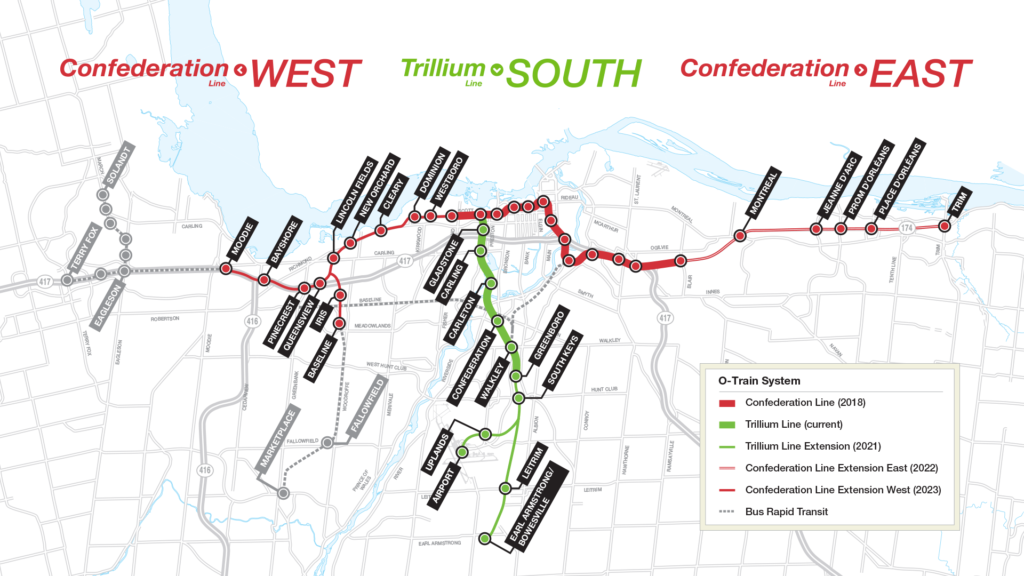

Ottawa has an existing rapid transit system that has dedicated roads for bus access. That system is being upgraded and, in part, replaced by the Confederation Line, a light rail transit system. The initial light rail system will be operating in 2018. There is a Stage 2 expansion that extends the Confederation Line east by 2022 and west by 2023, as well as extending the Trillium Line south by 2021. The map below shows the rapid transit system in full.

The broad stroke policy announcement is easy: 80% of the office buildings that PSPC has in its inventory will be oriented to rapid transit. “Oriented to rapid transit” means the building will be located within 600 metres of a rapid-transit stop. The hard part is, how does that affect private sector owners of office buildings?

The NCA office universe for government occupancy

A first consideration is that PSPC specifies “The NCA portfolio”. The National Capital Area (NCA) includes the employees housed in Ottawa and Gatineau in leased and owned office buildings. Gatineau has its own rapid-transit system as well, and it integrates with the Ottawa rapid-transit system. That means that the portfolio PSPC is looking to have oriented to rapid-transit can have buildings both in Ottawa and Gatineau.

A second point to be considered – is this a PSPC initiative, or is this a Treasury Board policy that applies to all the departments here including PSPC? If it is a Treasury Board policy, could that there require PSPC to make up for a shortfall in the 80/20 split if another group/department was unable to do so?

Treasury Board Secretariat, the central agency that sets policy for all departments who have custody for real estate and to whom these departments report for real estate performance, maintains the Directory of Federal Real Property. This directory is a compendium of all owned, leased and lease-purchase properties.

The summary above indicates that Ottawa houses civil servants in 40.3 million square feet of office space in the National Capital Area. PSPC has “custody” for 37.3 million square feet, or about 92.4% of the office space in the NCA occupied by the federal government.

The bucket of buildings that could be part of the 20% of the portfolio that does not provide rapid transit access totals 8,066,254 square feet from a Treasury Board NCA perspective, while PSPC has a target of at most 7,454,123 square feet. For the sake of simplicity, the Treasury Board target is 8 million square feet, while the PSPC target is 7.5 million square feet.

PRIVATE SECTOR IMPACT

Reverse Engineering approach

The buildings challenged by this policy are all those that are not oriented to rapid-transit access. The guideline for access is be within 600 metres of a rapid-transit station. Rapid transit station can be any of light rail stations, the dedicated bus transitway stations in Ottawa, and the bus rapid transit stations in Gatineau.

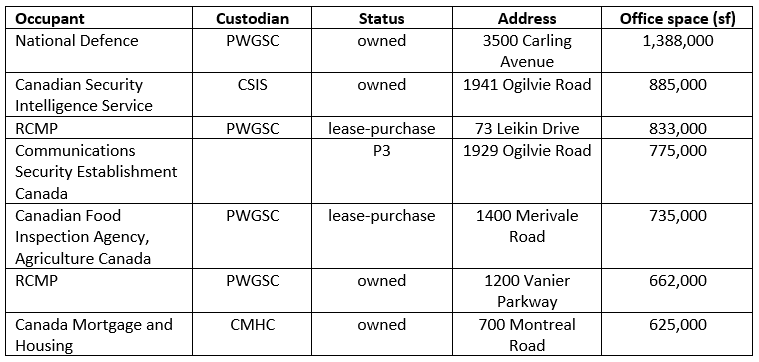

The reverse engineering we employ is to catalogue how many federal government properties are not within 600 metres of a rapid transit station and that they are unlikely to vacate. An example of this is the new Department of National Defence headquarters at 3500 Carling Avenue. There are office buildings or campuses, either leased, owned or lease-purchase, that the federal government is unlikely to leave because of this policy.

Once we have an idea about how much they will stay in, that way we determine just how much of that 20% is left over for anyone else.

How it is straightforward and how it is opaque

The straightforward government properties that fail this test include:

These properties are straightforward in that these properties look like office buildings and are identified as providing office space. They total 5.9 million square feet.

These properties include the new DND HQ at Carling and Moodie, a ten-building complex that DND is in the process of relocating to in what it describes as the largest corporate consolidation in Canadian history. What is a little puzzling is how a complex that was sold as 2,350,000 square feet now totals 1,388,000 square feet.

Some trickier properties include:

These properties are a little more difficult to quantify. They total 3,572,000 square feet.

The National Research Council has a campus in east end Ottawa. it has 88 buildings in the campus, with a total area of 2,570,000 square feet. Many of the buildings have some office component, and those buildings add up to 2,045,000 square feet. What is not clear is just what proportion of that area is office space, or whether only office space (as opposed to research and technological development, industrial, warehouse, storage, etc.) is counted for access to rapid transit.

The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) has centralized its operations at 333 River Road. CBSA was the target department to be housed at the 30 acres +/- of vacant land purchased by the federal government at 530 Tremblay Road, and that is across Highway 417 from the light rail transit station at St. Laurent Shopping Centre. While the private sector may consider a 10-15 year lease here to qualify as a long term hold, the federal government considers that to be a medium-term hold. Maybe this occupant is less sticky here given the 80/20 policy.

The Communications Research Centre is a campus just east of the Kanata North Business Park. it consists of 36 buildings providing primarily research and technological development space. If the count is for office space, then this facility has little impact on the remainder of the 20% bucket.

The Sir Charles Tupper Building is older and includes commercial retail, assemble and cultural, industrial, military and warehouse, storage and workshops in addition to its use for office space. It is included in this discussion as well as an older property that may be at the end of its economic life. The federal government owned portfolio has an average age of about 50 years. It s easy to imagine that the occupants are relocated to newer transit oriented buildings and this one is redeveloped.

If you are keeping score

Treasury Board straightforward: 5.9 million square feet

PSPC straightforward: 3.7 million square feet

Treasury Board straightforward + opaque: 9.6 million square feet

PSPC straightforward + opaque: 4.7 million square feet

Treasury Board has a portfolio that may not meet this requirement. PSPC likely has room in its 20% bucket for many existing buildings not meeting the rapid transit access policy.

NUANCES IN THE ISSUES RAISED

The problem of the declining denominator

There are two trends affecting demand by the federal government for office space: employee head count, and the allocation of office space per employee. The head count in Ottawa declined 2012 through about 2015 resulting from the efforts made by the previous government to “right-size” departments with reductions to budgets. That reduction to budgets meant less people employed. The most recent government has increased the head count. The following Treasury Board document points to the 20-year cycle for federal government head counts.

The head count reductions seem to occur about every 20 years, with the Chretien government downsizing in the mid-1990s being the precursor to the Harper government downsizing of the mid-2010s.

Head counts will increase at a gradual rate for the foreseeable future, however the efforts of PSPC to capture the efficiencies available from technology means that the office space footprint per employee results in less demand for office accommodations. This initiative is known as Workplace 2.0.

The impact of these initiatives from an allocation of 18 square metres per employee to 14 square metres per employee. That is a reduction of 22%. Workplace 3.0 has 8.5 work stations for every 10 employees, and that reduces demand another 15%. The government does not anticipant that all departments will fully implement Workplace 2.0 and 3.0.

The office demand trend line means the denominator (the size of the portfolio of office space owned, the number of leased and lease-purchase properties) will decline, with the result that demand for non- rapid transit access will decline as well.

This rate of decline is proving to be difficult to track and verify.

Just what is 600 m?

Access to a rapid transit station is a distance of at most 600 metres.

The above illustrates how that can be subject to interpretation. The arrow at the bottom right shows the approximate location of the Tremblay station of the Confederation Line of the first phase of light rail transit at the Via Rail Terminal. The arrow to the left shows the RCMP campus.

About 2/3s of the campus is inside the 600-metre radius drawn around the light rail transit station. The problem is, there is no way to walk there in anything less than 1,000 metres.

It takes some work to establish just what really is a 600 m walk away from rapid transit station. This example from a recent Request for Information shows how access is determined:

This method to interpret 600 metres of walking distance makes it much easier to determine if a building qualifies under that criteria. It is not clear which tool is to be used for determining distance. Google Maps is quick and easy, however it may not be accurate enough to be definitive when the measurement is very close to 600 metres.

What about timing?

It is not clear how the federal government plans to account for a rapid transit system that has major upgrades in 2018 and 2021-2023.

The Confederation Line is to be completed in 2018; the Trillium Line going south to the airport and Bowesville Road is to be completed in 2021; the eastern extension of the Confederation Line to Trim Road is to be completed 2022; and, the westward expansion of the Confederation Line to Moodie Drive is to be completed by 2023. There is a mismatch between the target date of 2021 by PSPC and when the expansion of the light rail transit system is scheduled for completion.

Another quibble for timing – when does the timing of the opening of the rapid transit station relate to the start date of the lease and occupancy date by the federal government department occupying the space? There can oftentimes be a period in which the space is leased and undergoing leasehold improvements for the department to occupy the building, so does access have to available for the lease start date or the date by which the occupants move in?

How is availability affected by the lease term to be agreed? What if the federal government is looking to secure accommodations for 10 years and the rapid transit station is not completed until a month later? What if the deal is done for future occupancy and the rapid transit station is delayed in completion and is not open when the lease starts or occupancy by the user group starts?

Summary

There is a declining demand from the federal government for office space not providing access to rapid transit stations. As the federal government has some pretty big office accommodations that it is unlikely to give up not meeting this requirement, there is even less capacity for the private sector to fill to meet this policy requirement.

And as happens every time, our investigations end up with less than adequate answers to what we seek to understand. There is nothing definitive we can point to that outlines who is left behind by this policy.